Analysis of the TITAN fall

Updated on June 21:

- Added low ECR as another cause of the incident.

- Added a reference to Frax Finance.

- Added an explanation of arbitraging.

- Fixed a bug in arbitraging profits calculations, which caused lower values.

Updated on June 22: Added ‘The full picture’ section. The analysis is now complete.

Introduction

This is an analysis of an incident that happened to Iron.Finance on June 16, 2021. As a result of the incident, the price of TITAN token has collapsed to 0 and the IRON stablecoin has lost its peg to USD and hasn’t regained it yet.

There are already multple reports on the incident ( one, two, three ). While these are good attempts, they didn’t answer the only question that inerested me: what part of the design has failed? And if it wasn’t a deisgn flaw, then why was it possible?

An official post-portem was published by Iron.Finance. While it gave some overview of what was happening on the market, it didn’t assume there were any problems in the design of the service. The team has called an unexpected bank-run the only culprit of the collapse:

We never thought it would happen, but it just did. We just experienced the world’s first large-scale crypto bank run.

I managed to collect some on-chain data and get a better picture of what has happened. Here’s my analysis and conclusions.

TL;DR This was a design flaw. Iron.Finance was designed for growth only, the stabilizing mechanism couldn’t work when TITAN was falling. TITAN prices provided by a price oracle were delayed and the gap between these prices and real-time prices made arbitraging unprofitable.

A brief introduction into Iron.Finance

Iron.Finance introduced a new type of stablecoins: a partially collateralized token, soft pegged to USD. On the Polygon network, the token was named IRON and it was partially collateralized by USDC; the other part was collateralized by TITAN, another token created by Iron.Finance. TITAN’s only utility was to be used as a collateral when minting IRON, it had no other uses and it had an infinite supply: there were no supply cap or minting rate limiting.

It’s worth noting that Iron Finance didn’t invent that new type of stablecoins. It was invented by Frax Finance. Iron Finance simply copied their smart contracts and modified them according to their vision.

Any user can issue IRON baked by their USDC and TITAN (which they bought from the market). The amount of issued IRONs was calculated as:

$$IRON_{amt} = (USDC_{amt} * USDC_{price}) + (TITAN_{amt} * TITAN_{price})$$

So, we can say that IRON was backed by a basket of USDC+TITAN and every issued IRON equaled to $1 worth of USDC+TITAN. Their proportion in the basket was determined by:

$$IRON_{value} = USDC_{value} * TCR + TITAN_{value} * (1 - TCR) $$

Where values are amounts multiplied by prices and \(TCR\) is Target Collateral Ratio. This ratio determined how much of USDC and TITAN you need to deposit to get IRON. On the day of the incident it was 70%, which meant you needed to provide 70 cents of USDC and 30 cents of TITAN to mint 1 IRON.

Burning IRON is also an option, it was called redeeming: you burn some amount of IRON in exchange for USDC+TITAN. This time, however, a different ratio was used to determine how much of USDC and TITAN you get: Effective Collateral Ratio (ECR), which was calculated as: $$ECR=\frac{totalValueUSDC}{totalSupplyIRON}$$ Where \(totalValueUSDC\) is the total value of USDC deposited in exchange for IRON tokens during minting and \(totalSupplyIRON\) is the total number of issued IRONs. ECR determines what percentage of issued IRON tokens is backed by USDC. On the day of the incident ECR was 75%.

To sum it up, both TCR and ECR determine ratios of USDC+TITAN when minting or redeeming IRON. TCR is used when minting, ECR is used when redeeming.

IRON stabilization mechanism

It’s not uncommon for a stablecoin to lose its peg. This usually happens when there’s a selling or buying pressure on the market. Thus, every stablecoin needs a mechanism of protection from such fluctuations. And IRON had one such mechanism.

Arbitrageurs were expected to stabilize the price of IRON because there was an incentive. If price goes down, they can buy cheap IRON from the market, redeem it for USDC+TITAN (1 IRON produces $1 worth of USDC+TITAN when redeeming) and sell TITAN for some profit. Such buying from the market would eventually rise the price of IRON.

On the other hand, if price goes up, they would mint new IRON (1 IRON requires $1 worth of USDC+TITAN when minting) and sell them on the market to get the difference as a profit. Selling would eventually drop the price of IRON.

This stabilization mechanism worked. And it worked (once) on the day when the incident happened.

Incident timeline

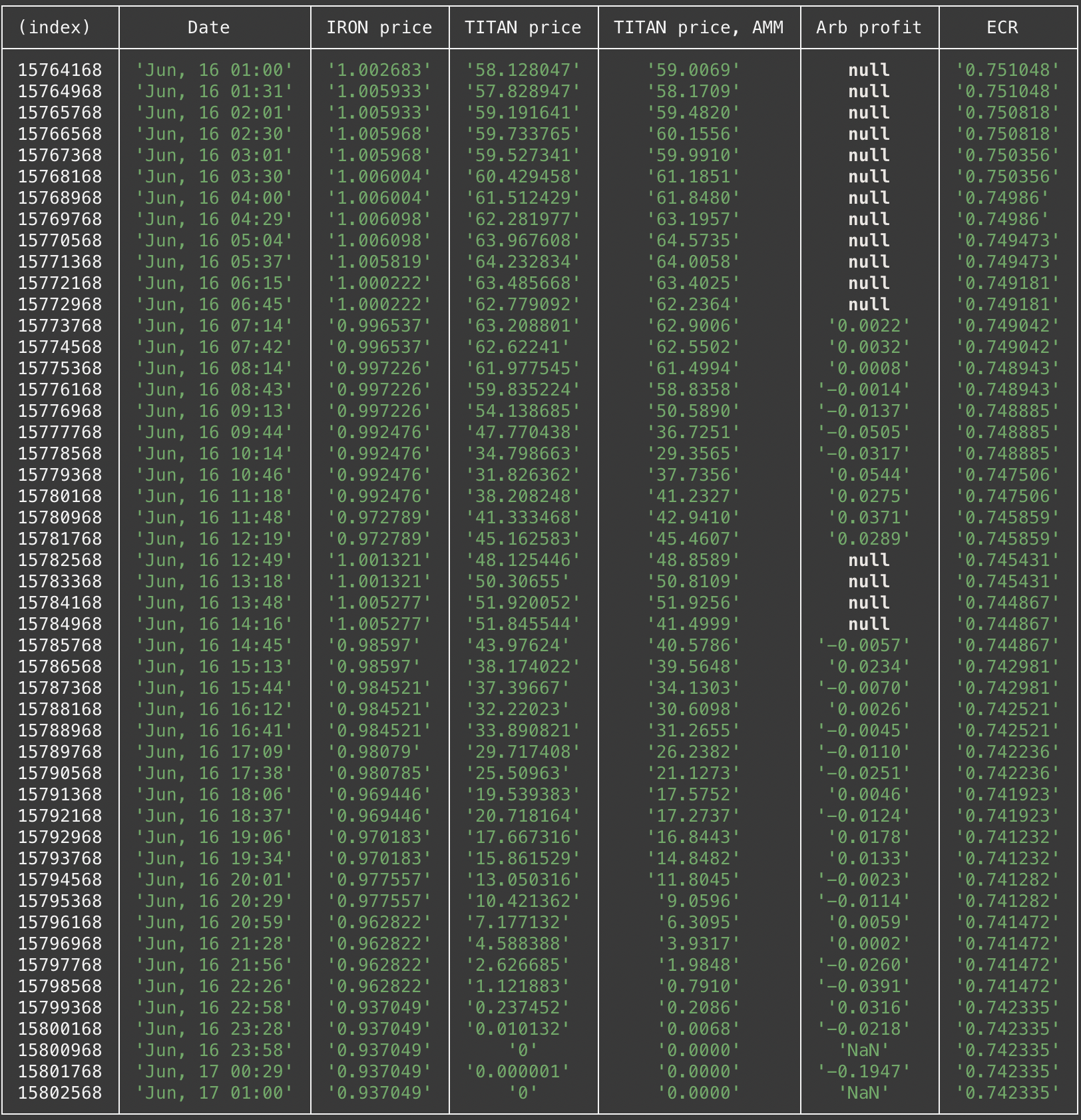

This is the on-chain data that I collected and that helped to find the flaw:

Update, June 21: first version of the table contained a bug that resulted in lower arbitraging profits.

Columns are:

- (index) - block numbers.

- Date, when the block was produced.

- IRON price - IRON prices obtained from a price oracle. These prices weren’t delayed by TWAP.

- TITAN price – TITAN prices obtained from a price oracle. These prices were delayed by a 60-minute TWAP (Time Weighted Average Price). TWAP was used here to protect from price manipulations caused by flash loan attacks.

- TITAN price, AMM – TITAN prices obtained from an Automated Market Maker (Sushi Swap). These are real-time prices, they go ‘before’ the prices in the TITAN price column.

- Arb profit – the profit arbitrageurs would get from trying to bump the price of IRON, i.e. buying IRON on the market, redeeming USDC+TITAN, and selling redeemed TITAN on the market. Fees are not included. Values in this column are only calculated when IRON price is below $1. This is the most important column.

- ECR – ECR is used in the arbitraging scheme explained above.

Everything looked good until around 7:14 AM: at this time, TITAN reached its peak price but IRON has gone a little below $1.

At around 10:46 AM, TITAN has reached its local bottom at $31.82. Before this moment, Arb profit stayed negative, which means there was no incentive for arbitrageurs to stabilize the price of IRON and it remained below $1.

At around 12:49 PM, IRON has returned to $1, which was caused the few positive arbitraging profits preceding this moment.

By around 1:48 PM, TITAN has bounced and reached its local top; IRON was also slightly above $1. What has happened from 7:14 AM until this moment looked like a big selling pressure which dropped the price of TITAN and caused IRON to lose its peg. Luckily, both TITAN and IRON seemed to recover after the sell-off. The stabilization mechanism has worked. However, those negative arbitraging profits looked worrisome.

What happened next was a catastrophe.

After 2 PM, TITAN was failing and eventually reached 0. IRON lost its peg and landed at around $0.94, which is a huge drop for a stablecoin. The Iron.Finance team had to pause minting and redeeming.

What happened to the stabilization mechanism? It had worked earlier on that day but somehow failed to save the tokens from collapsing during a new sell-off.

If you look at the Arb profit column, you will know the answer: arbitraging couldn’t provide profit consistently. Even though the price stayed below $1, profit wasn’t consistent during the sell-off. This means that arbitraging, which is a part of the stabiliziation mechanism, wasn’t always possible. As a result, there was not enough of buying pressure to bump the price.

There were two reasons why this happened.

The first reason is the delayed TITAN price oracle: because of the delay, TITAN prices obtained from the oracle and used to calculate the amount of TITAN tokens redeemed for IRON, were higher than those on AMM (real-time prices). That price gap made arbitraging unprofitable.

The other reason is low ECR. ECR is used in redeeming to determine the portion of TITAN you get. During the second sell-off, it equaled to 74%, which means 1 IRON was redeemed for 74 cents worth of USDC and 26 cents worth of TITAN. And this portion of TITAN was too big due to the price gap (the more TITAN you get the more money you lose selling it on the external market).

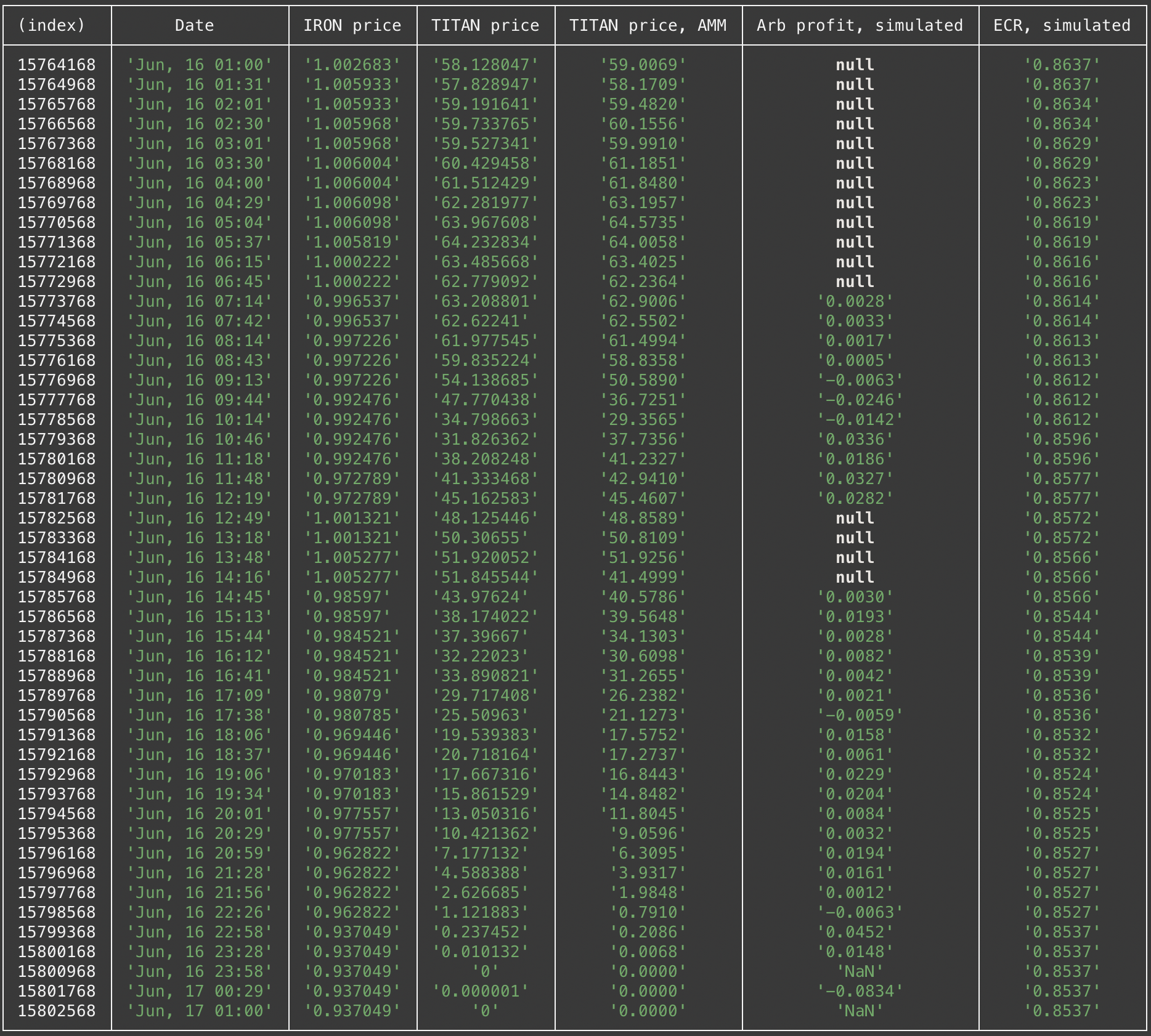

I ran a simulation which showed that an ECR increased by 15% would’ve made arbitraging profitable:

However, ECR is not designed to react to market changes, it only reflects the percentage of IRON tokens backed by USDC.

How arbitraging could save it

When IRON price goes below $1 there’s an incentive to buy it from the market. Remember minting and redeeming? They can be seen as an internal market. On this market, the price of IRON is always $1 and it can be bought only by a combination of USDC and TITAN.

Buying IRON from this internal market is minting: you deposit $1 worth of USDC+TITAN to get 1 IRON (which is always $1 in the internal market). Selling IRON to the internal market is redeeming: you burn some amount of IRON to get $1 worth of USDC+TITAN for every IRON burnt. When there are two markets with different prices, there are arbitraging opportunities. And there were, in fact, two markets: that internal one and an external one, which was an automated market maker (IRON was traded to WMATIC on SushiSwap).

So, it was expected that when IRON price goes below $1 on the external market, it would be profitable to buy it on it (because it’s cheaper there) and redeem it on the internal market (because it’s more expensive there). The profit would come from selling TITAN. And this expectation had played out during the first sell-off on that day.

However, it couldn’t kick-start during the second sell-off. There was not enough buying pressure on IRON to bump the price. And we now know the cause: arbitraging wasn’t profitable. Since TITAN was falling for a longer period and oracle prices was delayed, the actual value of TITAN tokens redeemed for IRON was lower than expected. Or in other words, the value of USDC+TITAN redeemed for IRON was lower than $1 (with fees it was even lower).

The full picture

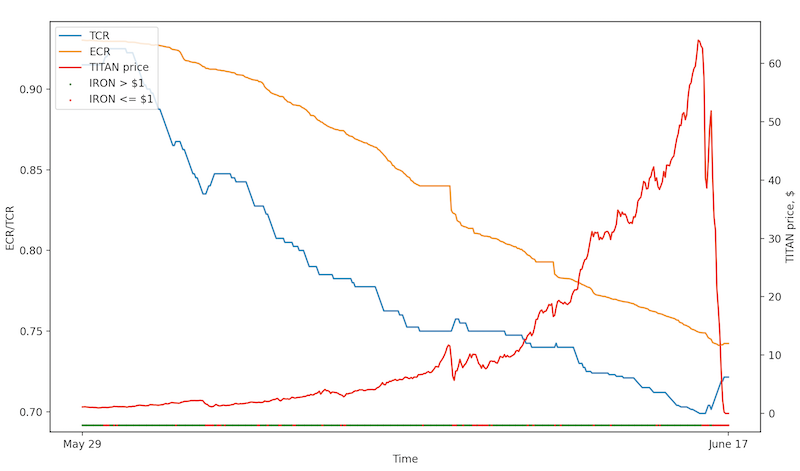

I’ve managed to reconstruct the full picture of the incident. Here are historical values of some key metrics collected since the launch of IRON and until the collapse:

Key patterns on this graph are:

- ECR and TCR were close to 100 when the project had launched.

- Both ECR and TCR were lowering during the lifetime of the project.

- IRON price had almost always been above $1 (green dots at the bottom).

As I explained earlier, by the time TITAN started falling on June 16, ECR was too low for arbitraging to be profitable. On top of that, a price gap caused by delayed oracle prices made it even less profitable. ECR is TCR averaged over time or minting events: ECR reflects accumulated amount of USDC, which is deposited in amounts defined by TCR. So, ECR followed TCR.

TCR, in its turn, is tied to IRON prices: if IRON costs more than $1 on the market, TCR lowers, reducing the amount of USDC required to mint IRON. And the opposite: if IRON costs less than $1, TCR grows increasing the amount of USDC required to mint IRON. The meaning of such connection is that when the demand for IRON rises (its price is growing) it should become less collateralized, which eventually reduces its price. On the other hand, when the demand for IRON lowers (its price is falling), it should have more collateral to have higher value.

Now, as you can see, IRON prices was almost constantly above $1 and TCR was almost always lowering. Why did it happen?

Remember how TWAP caused a price gap: while TITAN was falling, oracle prices were higher? Well, it turns out it works in the opposite direction as well: when TITAN is rising, oracle prices are lower than market ones. What this means is that when TITAN is growing, redeeming becomes profitable even if IRON costs more than $1. Since oracle prices are lower than market ones, redeeming results in a slightly bigger amount of TITAN tokens, which can be sold on the markets for profit.

So, this is what happened:

- TWAP and rising TITAN prices caused a prices gap: oracle prices were lower than market ones.

- Arbitraging bots were buying IRON from the market (for $1 or slightly more), redeeming it for TITAN, and selling TITAN for profit.

- TITAN price kept rising, bots kept arbitraging, IRON price stayed at or above $1.

- TCR was lowering and ECR was following it.

- Eventually, ECR got too low to make arbitraging profitable when TITAN started dropping and IRON went below $1.

Conclusion

While many called Iron.Finance a scam project, it doesn’t look like that to me. The timeline I built based on on-chain data has shown that the stabilization algorithm they built had worked – it managed to stabilize the price of IRON during the first sell-off. However, it failed during the second sell-off due to a design flaw: there were no incentive for arbitrageurs when TITAN token price was falling rapidly. I’d like to emphasize this: it wasn’t a code bug, it was a design flaw. The stabilization mechanism based on arbitraging they described on their website and implemented in smart contracts has failed because it couldn’t handle rapid price dropping of TITAN.

Was this an attack that abused the stabilization mechanism? To me, it doesn’t look so. There was no sole beneficiary from the incident besides those who sold TITAN on its all-time-high price. Price speculations are the nature of the markets and for DeFi project to be sustainable to speculations they have to design and implement solid mechanism, which wasn’t a case for Iron.Finance.

Related links

Huge thanks to Moralis, the analysis wouldn’t have been possible without them. It was hard to believe, but they provide access to Polygon archive nodes for free!

- The script I used to collect data and build the table

- Iron.Finance Documentation

- Iron.Finance Smart Contracts

- Iron Finance Implodes After ‘Bank Run’

- Looking at Iron Finance’s Failure

- What Actually Happened

Photo by

Photo by