Building Blockchain in Go. Part 4: Transactions 1

Chinese translations: by liuchengxu, by zhangli1

Introduction

Transactions are the heart of Bitcoin and the only purpose of blockchain is to store transactions in a secure and reliable way, so no one could modify them after they are created. Today we’re starting implementing transactions. But because this is quite a big topic, I’ll split it into two parts: in this part, we’ll implement the general mechanism of transactions and in the second part we’ll work through details.

Also, since code changes are massive, it makes no sense describing all of them here. You can see all the changes here.

There is no spoon

If you’ve ever developed a web application, in order to implement payments you would likely to create these tables in a DB: accounts and transactions. An account would store information about a user, including their personal information and balance, and a transaction would store information about money transferring from one account to another. In Bitcoin, payments are realized in completely different way. There are:

- No accounts.

- No balances.

- No addresses.

- No coins.

- No senders and receivers.

Since blockchain is a public and open database, we don’t want to store sensitive information about wallet owners. Coins are not collected in accounts. Transactions do not transfer money from one address to another. There’s no field or attribute that holds account balance. There are only transactions. But what’s inside a transaction?

Bitcoin Transaction

A transaction is a combination of inputs and outputs:

type Transaction struct {

ID []byte

Vin []TXInput

Vout []TXOutput

}

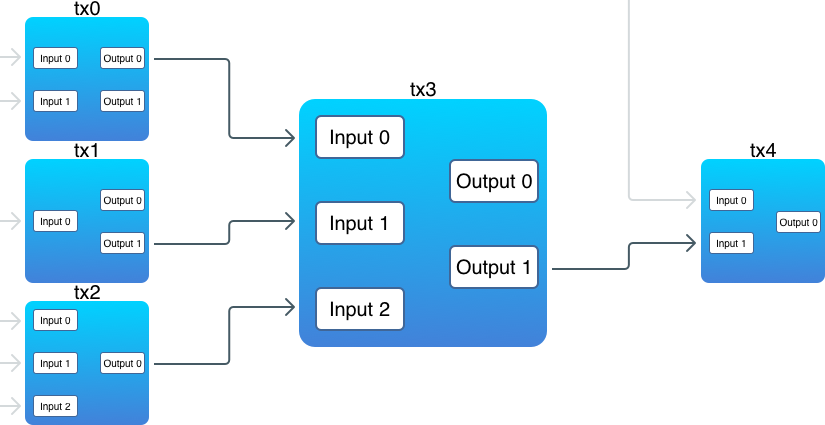

Inputs of a new transaction reference outputs of a previous transaction (there’s an exception though, which we’ll discuss later). Outputs are where coins are actually stored. The following diagram demonstrates the interconnection of transactions:

Notice that:

- There are outputs that are not linked to inputs.

- In one transaction, inputs can reference outputs from multiple transactions.

- An input must reference an output.

Throughout this article, we’ll use words like “money”, “coins”, “spend”, “send”, “account”, etc. But there are no such concepts in Bitcoin. Transactions just lock values with a script, which can be unlocked only by the one who locked them.

Transaction Outputs

Let’s start with outputs first:

type TXOutput struct {

Value int

ScriptPubKey string

}

Actually, it’s outputs that store “coins” (notice the Value field above). And storing means locking them with a puzzle, which is stored in the ScriptPubKey. Internally, Bitcoin uses a scripting language called Script, that is used to define outputs locking and unlocking logic. The language is quite primitive (this is made intentionally, to avoid possible hacks and misuses), but we won’t discuss it in details. You can find a detailed explanation of it here.

In Bitcoin, the value field stores the number of satoshis, not the number of BTC. A satoshi is a hundred millionth of a bitcoin (0.00000001 BTC), thus this is the smallest unit of currency in Bitcoin (like a cent).

Since we don’t have addresses implemented, we’ll avoid the whole scripting related logic for now. ScriptPubKey will store an arbitrary string (user defined wallet address).

By the way, having such scripting language means that Bitcoin can be used as a smart-contract platform as well.

One important thing about outputs is that they are indivisible, which means that you cannot reference a part of its value. When an output is referenced in a new transaction, it’s spent as a whole. And if its value is greater than required, a change is generated and sent back to the sender. This is similar to a real world situation when you pay, say, a $5 banknote for something that costs $1 and get a change of $4.

Transaction Inputs

And here’s the input:

type TXInput struct {

Txid []byte

Vout int

ScriptSig string

}

As mentioned earlier, an input references a previous output: Txid stores the ID of such transaction, and Vout stores an index of an output in the transaction. ScriptSig is a script which provides data to be used in an output’s ScriptPubKey. If the data is correct, the output can be unlocked, and its value can be used to generate new outputs; if it’s not correct, the output cannot be referenced in the input. This is the mechanism that guarantees that users cannot spend coins belonging to other people.

Again, since we don’t have addresses implemented yet, ScriptSig will store just an arbitrary user defined wallet address. We’ll implement public keys and signatures checking in the next article.

Let’s sum it up. Outputs are where “coins” are stored. Each output comes with an unlocking script, which determines the logic of unlocking the output. Every new transaction must have at least one input and output. An input references an output from a previous transaction and provides data (the ScriptSig field) that is used in the output’s unlocking script to unlock it and use its value to create new outputs.

But what came first: inputs or outputs?

The egg

In Bitcoin, it’s the egg that came before the chicken. The inputs-referencing-outputs logic is the classical “chicken or the egg” situation: inputs produce outputs and outputs make inputs possible. And in Bitcoin, outputs come before inputs.

When a miner starts mining a block, it adds a coinbase transaction to it. A coinbase transaction is a special type of transactions, which doesn’t require previously existing outputs. It creates outputs (i.e., “coins”) out of nowhere. The egg without a chicken. This is the reward miners get for mining new blocks.

As you know, there’s the genesis block in the beginning of a blockchain. It’s this block that generates the very first output in the blockchain. And no previous outputs are required since there are no previous transactions and no such outputs.

Let’s create a coinbase transaction:

func NewCoinbaseTX(to, data string) *Transaction {

if data == "" {

data = fmt.Sprintf("Reward to '%s'", to)

}

txin := TXInput{[]byte{}, -1, data}

txout := TXOutput{subsidy, to}

tx := Transaction{nil, []TXInput{txin}, []TXOutput{txout}}

tx.SetID()

return &tx

}

A coinbase transaction has only one input. In our implementation its Txid is empty and Vout equals to -1. Also, a coinbase transaction doesn’t store a script in ScriptSig. Instead, arbitrary data is stored there.

In Bitcoin, the very first coinbase transaction contains the following message: “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks”. You can see it yourself.

subsidy is the amount of reward. In Bitcoin, this number is not stored anywhere and calculated based only on the total number of blocks: the number of blocks is divided by 210000. Mining the genesis block produced 50 BTC, and every 210000 blocks the reward is halved. In our implementation, we’ll store the reward as a constant (at least for now 😉 ).

Storing Transactions in Blockchain

From now on, every block must store at least one transaction and it’s no more possible to mine blocks without transactions. This means that we should remove the Data field of Block and store transactions instead:

type Block struct {

Timestamp int64

Transactions []*Transaction

PrevBlockHash []byte

Hash []byte

Nonce int

}

NewBlock and NewGenesisBlock also must be changed accordingly:

func NewBlock(transactions []*Transaction, prevBlockHash []byte) *Block {

block := &Block{time.Now().Unix(), transactions, prevBlockHash, []byte{}, 0}

...

}

func NewGenesisBlock(coinbase *Transaction) *Block {

return NewBlock([]*Transaction{coinbase}, []byte{})

}

Next thing to change is the creation of a new blockchain:

func CreateBlockchain(address string) *Blockchain {

...

err = db.Update(func(tx *bolt.Tx) error {

cbtx := NewCoinbaseTX(address, genesisCoinbaseData)

genesis := NewGenesisBlock(cbtx)

b, err := tx.CreateBucket([]byte(blocksBucket))

err = b.Put(genesis.Hash, genesis.Serialize())

...

})

...

}

Now, the function takes an address which will receive the reward for mining the genesis block.

Proof-of-Work

The Proof-of-Work algorithm must consider transactions stored in a block, to guarantee the consistency and reliability of blockchain as a storage of transaction. So now we must modify the ProofOfWork.prepareData method:

func (pow *ProofOfWork) prepareData(nonce int) []byte {

data := bytes.Join(

[][]byte{

pow.block.PrevBlockHash,

pow.block.HashTransactions(), // This line was changed

IntToHex(pow.block.Timestamp),

IntToHex(int64(targetBits)),

IntToHex(int64(nonce)),

},

[]byte{},

)

return data

}

Instead of pow.block.Data we now use pow.block.HashTransactions() which is:

func (b *Block) HashTransactions() []byte {

var txHashes [][]byte

var txHash [32]byte

for _, tx := range b.Transactions {

txHashes = append(txHashes, tx.ID)

}

txHash = sha256.Sum256(bytes.Join(txHashes, []byte{}))

return txHash[:]

}

Again, we’re using hashing as a mechanism of providing unique representation of data. We want all transactions in a block to be uniquely identified by a single hash. To achieve this, we get hashes of each transaction, concatenate them, and get a hash of the concatenated combination.

Bitcoin uses a more elaborate technique: it represents all transactions containing in a block as a Merkle tree and uses the root hash of the tree in the Proof-of-Work system. This approach allows to quickly check if a block contains certain transaction, having only just the root hash and without downloading all the transactions.

Let’s check that everything is correct so far:

$ blockchain_go createblockchain -address Ivan

00000093450837f8b52b78c25f8163bb6137caf43ff4d9a01d1b731fa8ddcc8a

Done!

Good! We received out first mining reward. But how do we check the balance?

Unspent Transaction Outputs

We need to find all unspent transaction outputs (UTXO). Unspent means that these outputs weren’t referenced in any inputs. On the diagram above, these are:

- tx0, output 1;

- tx1, output 0;

- tx3, output 0;

- tx4, output 0.

Of course, when we check balance, we don’t need all of them, but only those that can be unlocked by the key we own (currently we don’t have keys implemented and will use user defined addresses instead). First, let’s define locking-unlocking methods on inputs and outputs:

func (in *TXInput) CanUnlockOutputWith(unlockingData string) bool {

return in.ScriptSig == unlockingData

}

func (out *TXOutput) CanBeUnlockedWith(unlockingData string) bool {

return out.ScriptPubKey == unlockingData

}

Here we just compare the script fields with unlockingData. These pieces will be improved in a future article, after we implement addresses based on private keys.

The next step - finding transactions containing unspent outputs - is quite difficult:

func (bc *Blockchain) FindUnspentTransactions(address string) []Transaction {

var unspentTXs []Transaction

spentTXOs := make(map[string][]int)

bci := bc.Iterator()

for {

block := bci.Next()

for _, tx := range block.Transactions {

txID := hex.EncodeToString(tx.ID)

Outputs:

for outIdx, out := range tx.Vout {

// Was the output spent?

if spentTXOs[txID] != nil {

for _, spentOut := range spentTXOs[txID] {

if spentOut == outIdx {

continue Outputs

}

}

}

if out.CanBeUnlockedWith(address) {

unspentTXs = append(unspentTXs, *tx)

}

}

if tx.IsCoinbase() == false {

for _, in := range tx.Vin {

if in.CanUnlockOutputWith(address) {

inTxID := hex.EncodeToString(in.Txid)

spentTXOs[inTxID] = append(spentTXOs[inTxID], in.Vout)

}

}

}

}

if len(block.PrevBlockHash) == 0 {

break

}

}

return unspentTXs

}

Since transactions are stored in blocks, we have to check every block in a blockchain. We start with outputs:

if out.CanBeUnlockedWith(address) {

unspentTXs = append(unspentTXs, tx)

}

If an output was locked by the same address we’re searching unspent transaction outputs for, then this is the output we want. But before taking it, we need to check if an output was already referenced in an input:

if spentTXOs[txID] != nil {

for _, spentOut := range spentTXOs[txID] {

if spentOut == outIdx {

continue Outputs

}

}

}

We skip those that were referenced in inputs (their values were moved to other outputs, thus we cannot count them). After checking outputs we gather all inputs that could unlock outputs locked with the provided address (this doesn’t apply to coinbase transactions, since they don’t unlock outputs):

if tx.IsCoinbase() == false {

for _, in := range tx.Vin {

if in.CanUnlockOutputWith(address) {

inTxID := hex.EncodeToString(in.Txid)

spentTXOs[inTxID] = append(spentTXOs[inTxID], in.Vout)

}

}

}

The function returns a list of transactions containing unspent outputs. To calculate balance we need one more function that takes the transactions and returns only outputs:

func (bc *Blockchain) FindUTXO(address string) []TXOutput {

var UTXOs []TXOutput

unspentTransactions := bc.FindUnspentTransactions(address)

for _, tx := range unspentTransactions {

for _, out := range tx.Vout {

if out.CanBeUnlockedWith(address) {

UTXOs = append(UTXOs, out)

}

}

}

return UTXOs

}

That’s it! Now we can implement getbalance command:

func (cli *CLI) getBalance(address string) {

bc := NewBlockchain(address)

defer bc.db.Close()

balance := 0

UTXOs := bc.FindUTXO(address)

for _, out := range UTXOs {

balance += out.Value

}

fmt.Printf("Balance of '%s': %d\n", address, balance)

}

The account balance is the sum of values of all unspent transaction outputs locked by the account address.

Let’s check our balance after mining the genesis block:

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address Ivan

Balance of 'Ivan': 10

This is our first money!

Sending Coins

Now, we want to send some coins to someone else. For this, we need to create a new transaction, put it in a block, and mine the block. So far, we implemented only the coinbase transaction (which is a special type of transactions), now we need a general transaction:

func NewUTXOTransaction(from, to string, amount int, bc *Blockchain) *Transaction {

var inputs []TXInput

var outputs []TXOutput

acc, validOutputs := bc.FindSpendableOutputs(from, amount)

if acc < amount {

log.Panic("ERROR: Not enough funds")

}

// Build a list of inputs

for txid, outs := range validOutputs {

txID, err := hex.DecodeString(txid)

for _, out := range outs {

input := TXInput{txID, out, from}

inputs = append(inputs, input)

}

}

// Build a list of outputs

outputs = append(outputs, TXOutput{amount, to})

if acc > amount {

outputs = append(outputs, TXOutput{acc - amount, from}) // a change

}

tx := Transaction{nil, inputs, outputs}

tx.SetID()

return &tx

}

Before creating new outputs, we first have to find all unspent outputs and ensure that they store enough value. This is what FindSpendableOutputs method does. After that, for each found output an input referencing it is created. Next, we create two outputs:

- One that’s locked with the receiver address. This is the actual transferring of coins to other address.

- One that’s locked with the sender address. This is a change. It’s only created when unspent outputs hold more value than required for the new transaction. Remember: outputs are indivisible.

FindSpendableOutputs method is based on the FindUnspentTransactions method we defined earlier:

func (bc *Blockchain) FindSpendableOutputs(address string, amount int) (int, map[string][]int) {

unspentOutputs := make(map[string][]int)

unspentTXs := bc.FindUnspentTransactions(address)

accumulated := 0

Work:

for _, tx := range unspentTXs {

txID := hex.EncodeToString(tx.ID)

for outIdx, out := range tx.Vout {

if out.CanBeUnlockedWith(address) && accumulated < amount {

accumulated += out.Value

unspentOutputs[txID] = append(unspentOutputs[txID], outIdx)

if accumulated >= amount {

break Work

}

}

}

}

return accumulated, unspentOutputs

}

The method iterates over all unspent transactions and accumulates their values. When the accumulated value is more or equals to the amount we want to transfer, it stops and returns the accumulated value and output indices grouped by transaction IDs. We don’t want to take more than we’re going to spend.

Now we can modify the Blockchain.MineBlock method:

func (bc *Blockchain) MineBlock(transactions []*Transaction) {

...

newBlock := NewBlock(transactions, lastHash)

...

}

Finally, let’s implement send command:

func (cli *CLI) send(from, to string, amount int) {

bc := NewBlockchain(from)

defer bc.db.Close()

tx := NewUTXOTransaction(from, to, amount, bc)

bc.MineBlock([]*Transaction{tx})

fmt.Println("Success!")

}

Sending coins means creating a transaction and adding it to the blockchain via mining a block. But Bitcoin doesn’t do this immediately (as we do). Instead, it puts all new transactions into memory pool (or mempool), and when a miner is ready to mine a block, it takes all transactions from the mempool and creates a candidate block. Transactions become confirmed only when a block containing them is mined and added to the blockchain.

Let’s check that sending coins works:

$ blockchain_go send -from Ivan -to Pedro -amount 6

00000001b56d60f86f72ab2a59fadb197d767b97d4873732be505e0a65cc1e37

Success!

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address Ivan

Balance of 'Ivan': 4

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address Pedro

Balance of 'Pedro': 6

Nice! Now, let’s create more transactions and ensure that sending from multiple outputs works fine:

$ blockchain_go send -from Pedro -to Helen -amount 2

00000099938725eb2c7730844b3cd40209d46bce2c2af9d87c2b7611fe9d5bdf

Success!

$ blockchain_go send -from Ivan -to Helen -amount 2

000000a2edf94334b1d94f98d22d7e4c973261660397dc7340464f7959a7a9aa

Success!

Now, Helen’s coins are locked in two outputs: one from Pedro and one from Ivan. Let’s send them to someone else:

$ blockchain_go send -from Helen -to Rachel -amount 3

000000c58136cffa669e767b8f881d16e2ede3974d71df43058baaf8c069f1a0

Success!

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address Ivan

Balance of 'Ivan': 2

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address Pedro

Balance of 'Pedro': 4

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address Helen

Balance of 'Helen': 1

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address Rachel

Balance of 'Rachel': 3

Looks fine! Now let’s test a failure:

$ blockchain_go send -from Pedro -to Ivan -amount 5

panic: ERROR: Not enough funds

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address Pedro

Balance of 'Pedro': 4

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address Ivan

Balance of 'Ivan': 2

Conclusion

Phew! It wasn’t easy, but we have transactions now! Although, some key features of a Bitcoin-like cryptocurrency are missing:

- Addresses. We don’t have real, private key based addresses yet.

- Rewards. Mining blocks is absolutely not profitable!

- UTXO set. Getting balance requires scanning the whole blockchain, which can take very long time when there are many and many blocks. Also, it can take a lot of time if we want to validate later transactions. UTXO set is intended to solve these problems and make operations with transactions fast.

- Mempool. This is where transactions are stored before being packed in a block. In our current implementation, a block contains only one transaction, and this is quite inefficient.

Links: