Building Blockchain in Go. Part 7: Network

Chinese translations: by liuchengxu, by zhangli1

Introduction

So far, we’ve build a blockchain that has all key features: anonymous, secure, and randomly generated addresses; blockchain data storage; Proof-of-Work system; reliable way to store transactions. While these features are crucial, it’s not enough. What makes these features really shine, and what make cryptocurrencies possible, is network. What’s the use of having such blockchain implementation running just on a single computer? What’s the use of those cryptography based features, when there’s just one user? It’s network that make all these mechanism work and be useful.

You can think of those blockchain features as rules, similar to the rules that people establish when they want to live and thrive together. A kind of social arrangements. Blockchain network is a community of programs that follow the same rules, and it’s this following the rules that makes the network alive. Similarly, when people share identical ideas, they become stronger and can together build a better life. If there are people that follow a different set of rules, they’ll live in a separate society (state, commune, etc.). Identically, if there’re blockchain nodes that follow different rules, they’ll form a separate network.

This is very important: without a network and without a majority of nodes sharing identical rules, these rules are useless!

DISCLAIMER: Unfortunately, I didn’t have enough time to implement a real P2P network prototype. In this article I’ll demonstrate a most common scenario, that involves nodes of different types. Improving this scenario and making this a P2P network can be a good challenge and practice for you! Also I cannot guarantee that other scenarios besides the one implemented in this article, will work. Sorry!

This part introduces significant code changes, so it makes no sense explaining all of them here. Please refer to this page to see all the changes since the last article.

Blockchain Network

Blockchain network is decentralized, which means there’re no servers that do stuff and clients that use servers to get or process data. In blockchain network there are nodes, and each node is a full-fledged member of the network. A node is everything: it’s both a client and a server. This is very important to keep in mind, because it’s very different from usual web applications.

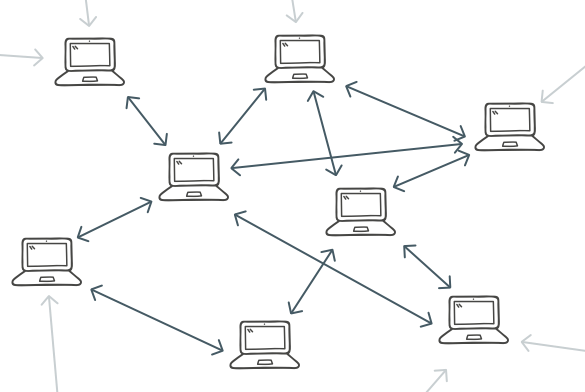

Blockchain network is a P2P (Peer-to-Peer) network, which means that nodes are connected directly to each other. It’s topology is flat, since there are no hierarchy in node roles. Here its schematic representation:

(Business vector created by Dooder - Freepik.com)

(Business vector created by Dooder - Freepik.com)

Nodes in such network are more difficult to implement, because they have to perform a lot of operations. Each node must interact with multiple other nodes, it must request other node’s state, compare it with it’s own state, and update its state when it’s outdated.

Node Roles

Despite being full-fledged, blockchain nodes can play different roles in the network. Here they are:

- Miner.

Such nodes are run on powerful or specialized hardware (like ASIC), and their only goal is to mine new blocks as fast as possible. Miners are only possible in blockchains that use Proof-of-Work, because mining actually means solving PoW puzzles. In Proof-of-Stake blockchains, for example, there’s no mining. - Full node.

These nodes validate blocks mined by miners and verify transactions. To do this, they must have the whole copy of blockchain. Also, such nodes perform such routing operations, like helping other nodes to discover each other.

It’s very crucial for network to have many full nodes, because it’s these nodes that make decisions: they decide if a block or transaction is valid. - SPV.

SPV stands for Simplified Payment Verification. These nodes don’t store a full copy of blockchain, but they still able to verify transactions (not all of them, but a subset, for example, those that were sent to specific address). An SPV node depends on a full node to get data from, and there could be many SPV nodes connected to one full node. SPV makes wallet applications possible: one don’t need to download full blockchain, but still can verify their transactions.

Network simplification

To implement network in our blockchain, we have to simplify some things. The problem is that we don’t have many computers to simulate a network with multiple nodes. We could’ve used virtual machines or Docker to solve this problem, but it could make everything more difficult: you would have to solve possible virtual machine or Docker issues, while my goal is to concentrate on blockchain implementation only. So, we want to run multiple blockchain nodes on a single machine and at the same time we want them to have different addresses. To achieve this we’ll use ports as node identifiers, instead of IP addresses. E.g., there will be nodes with addresses: 127.0.0.1:3000, 127.0.0.1:3001, 127.0.0.1:3002, etc. We’ll call the port node ID and use NODE_ID environment variable to set them. Thus, you can open multiple terminal windows, set different NODE_IDs and have different nodes running.

This approach also requires having different blockchains and wallet files. They now must depend on the node ID and be named like blockchain_3000.db, blockchain_30001.db and wallet_3000.db, wallet_30001.db, etc.

Implementation

So, what happens when you download, say, Bitcoin Core and run it for the first time? It has to connect to some node to downloaded the latest state of the blockchain. Considering that your computer is not aware of all, or some, Bitcoin nodes, what’s this node?

Hardcoding a node address in Bitcoin Core would’ve been a mistake: the node could be attacked or shut down, which could result in new nodes not being able to join the network. Instead, in Bitcoin Core, there are DNS seeds hardcoded. These are not nodes, but DNS servers that know addresses of some nodes. When you start a clean Bitcoin Core, it’ll connect to one of the seeds and get a list of full nodes, which it’ll then download the blockchain from.

In our implementation, there will be centralization though. We’ll have three nodes:

- The central node. This is the node all other nodes will connect to, and this is the node that’ll sends data between other nodes.

- A miner node. This node will store new transactions in mempool and when there’re enough of transactions, it’ll mine a new block.

- A wallet node. This node will be used to send coins between wallets. Unlike SPV nodes though, it’ll store a full copy of blockchain.

The Scenario

The goal of this article is to implement the following scenario:

- The central node creates a blockchain.

- Other (wallet) node connects to it and downloads the blockchain.

- One more (miner) node connects to the central node and downloads the blockchain.

- The wallet node creates a transaction.

- The miner nodes receives the transaction and keeps it in its memory pool.

- When there are enough transactions in the memory pool, the miner starts mining a new block.

- When a new block is mined, it’s send to the central node.

- The wallet node synchronizes with the central node.

- User of the wallet node checks that their payment was successful.

This is what it looks like in Bitcoin. Even though we’re not going to build a real P2P network, we’re going to implement a real, and the main and most important, use case of Bitcoin.

version

Nodes communicate by the means of messages. When a new node is run, it gets several nodes from a DNS seed, and sends them version message, which in our implementation will look like this:

type version struct {

Version int

BestHeight int

AddrFrom string

}

We have only one blockchain version, so the Version field won’t keep any important information. BestHeight stores the length of the node’s blockchain. AddFrom stores the address of the sender.

What should a node that receives a version message do? It’ll respond with its own version message. This is a kind of a handshake: no other interaction is possible without prior greeting of each other. But it’s not just politeness: version is used to find a longer blockchain. When a node receives a version message it checks if the node’s blockchain is longer than the value of BestHeight. If it’s not, the node will request and download missing blocks.

In order to receive message, we need a server:

var nodeAddress string

var knownNodes = []string{"localhost:3000"}

func StartServer(nodeID, minerAddress string) {

nodeAddress = fmt.Sprintf("localhost:%s", nodeID)

miningAddress = minerAddress

ln, err := net.Listen(protocol, nodeAddress)

defer ln.Close()

bc := NewBlockchain(nodeID)

if nodeAddress != knownNodes[0] {

sendVersion(knownNodes[0], bc)

}

for {

conn, err := ln.Accept()

go handleConnection(conn, bc)

}

}

First, we hardcode the address of the central node: every node must know where to connect to initially. minerAddress argument specifies the address to receive mining rewards to. This piece:

if nodeAddress != knownNodes[0] {

sendVersion(knownNodes[0], bc)

}

Means that if current node is not the central one, it must send version message to the central node to find out if its blockchain is outdated.

func sendVersion(addr string, bc *Blockchain) {

bestHeight := bc.GetBestHeight()

payload := gobEncode(version{nodeVersion, bestHeight, nodeAddress})

request := append(commandToBytes("version"), payload...)

sendData(addr, request)

}

Our messages, on the lower level, are sequences of bytes. First 12 bytes specify command name (“version” in this case), and the latter bytes will contain gob-encoded message structure. commandToBytes looks like this:

func commandToBytes(command string) []byte {

var bytes [commandLength]byte

for i, c := range command {

bytes[i] = byte(c)

}

return bytes[:]

}

It creates a 12-byte buffer and fills it with the command name, leaving rest bytes empty. There’s an opposite function:

func bytesToCommand(bytes []byte) string {

var command []byte

for _, b := range bytes {

if b != 0x0 {

command = append(command, b)

}

}

return fmt.Sprintf("%s", command)

}

When a node receives a command, it runs bytesToCommand to extract command name and processes command body with correct handler:

func handleConnection(conn net.Conn, bc *Blockchain) {

request, err := ioutil.ReadAll(conn)

command := bytesToCommand(request[:commandLength])

fmt.Printf("Received %s command\n", command)

switch command {

...

case "version":

handleVersion(request, bc)

default:

fmt.Println("Unknown command!")

}

conn.Close()

}

Ok, this is what the version command handler looks like:

func handleVersion(request []byte, bc *Blockchain) {

var buff bytes.Buffer

var payload verzion

buff.Write(request[commandLength:])

dec := gob.NewDecoder(&buff)

err := dec.Decode(&payload)

myBestHeight := bc.GetBestHeight()

foreignerBestHeight := payload.BestHeight

if myBestHeight < foreignerBestHeight {

sendGetBlocks(payload.AddrFrom)

} else if myBestHeight > foreignerBestHeight {

sendVersion(payload.AddrFrom, bc)

}

if !nodeIsKnown(payload.AddrFrom) {

knownNodes = append(knownNodes, payload.AddrFrom)

}

}

First, we need to decode the request and extract the payload. This is similar to all the handlers, so I’ll omit this piece in the future code snippets.

Then a node compares its BestHeight with the one from the message. If the node’s blockchain is longer, it’ll reply with version message; otherwise, it’ll send getblocks message.

getblocks

type getblocks struct {

AddrFrom string

}

getblocks means “show me what blocks you have” (in Bitcoin, it’s more complex). Pay attention, it doesn’t say “give me all your blocks”, instead it requests a list of block hashes. This is done to reduce network load, because blocks can be downloaded from different nodes, and we don’t want to download dozens of gigabytes from one node.

Handling the command as easy as:

func handleGetBlocks(request []byte, bc *Blockchain) {

...

blocks := bc.GetBlockHashes()

sendInv(payload.AddrFrom, "block", blocks)

}

In our simplified implementation, it’ll return all block hashes.

inv

type inv struct {

AddrFrom string

Type string

Items [][]byte

}

Bitcoin uses inv to show other nodes what blocks or transactions current node has. Again, it doesn’t contain whole blocks and transactions, just their hashes. The Type field says whether these are blocks or transactions.

Handling inv is more difficult:

func handleInv(request []byte, bc *Blockchain) {

...

fmt.Printf("Recevied inventory with %d %s\n", len(payload.Items), payload.Type)

if payload.Type == "block" {

blocksInTransit = payload.Items

blockHash := payload.Items[0]

sendGetData(payload.AddrFrom, "block", blockHash)

newInTransit := [][]byte{}

for _, b := range blocksInTransit {

if bytes.Compare(b, blockHash) != 0 {

newInTransit = append(newInTransit, b)

}

}

blocksInTransit = newInTransit

}

if payload.Type == "tx" {

txID := payload.Items[0]

if mempool[hex.EncodeToString(txID)].ID == nil {

sendGetData(payload.AddrFrom, "tx", txID)

}

}

}

If blocks hashes are transferred, we want to save them in blocksInTransit variable to track downloaded blocks. This allows us to download blocks from different nodes.

Right after putting blocks into the transit state, we send getdata command to the sender of the inv message and update blocksInTransit. In a real P2P network, we would want to transfer blocks from different nodes.

In our implementation, we’ll never send inv with multiple hashes. That’s why when payload.Type == "tx" only the first hash is taken. Then we check if we already have the hash in our mempool, and if not, getdata message is sent.

getdata

type getdata struct {

AddrFrom string

Type string

ID []byte

}

getdata is a request for certain block or transaction, and it can contain only one block/transaction ID.

func handleGetData(request []byte, bc *Blockchain) {

...

if payload.Type == "block" {

block, err := bc.GetBlock([]byte(payload.ID))

sendBlock(payload.AddrFrom, &block)

}

if payload.Type == "tx" {

txID := hex.EncodeToString(payload.ID)

tx := mempool[txID]

sendTx(payload.AddrFrom, &tx)

}

}

The handler is straightforward: if they request a block, return the block; if they request a transaction, return the transaction. Notice, that we don’t check if we actually have this block or transaction. This is a flaw :)

block and tx

type block struct {

AddrFrom string

Block []byte

}

type tx struct {

AddFrom string

Transaction []byte

}

It’s these messages that actually transfer the data.

Handling the block message is easy:

func handleBlock(request []byte, bc *Blockchain) {

...

blockData := payload.Block

block := DeserializeBlock(blockData)

fmt.Println("Recevied a new block!")

bc.AddBlock(block)

fmt.Printf("Added block %x\n", block.Hash)

if len(blocksInTransit) > 0 {

blockHash := blocksInTransit[0]

sendGetData(payload.AddrFrom, "block", blockHash)

blocksInTransit = blocksInTransit[1:]

} else {

UTXOSet := UTXOSet{bc}

UTXOSet.Reindex()

}

}

When we received a new block, we put it into our blockchain. If there’re more blocks to download, we request them from the same node we downloaded the previous block. When we finally downloaded all the blocks, the UTXO set is reindexed.

TODO: Instead of trusting unconditionally, we should validate every incoming block before adding it to the blockchain.

TODO: Instead of running UTXOSet.Reindex(), UTXOSet.Update(block) should be used, because if blockchain is big, it’ll take a lot of time to reindex the whole UTXO set.

Handling tx messages is the most difficult part:

func handleTx(request []byte, bc *Blockchain) {

...

txData := payload.Transaction

tx := DeserializeTransaction(txData)

mempool[hex.EncodeToString(tx.ID)] = tx

if nodeAddress == knownNodes[0] {

for _, node := range knownNodes {

if node != nodeAddress && node != payload.AddFrom {

sendInv(node, "tx", [][]byte{tx.ID})

}

}

} else {

if len(mempool) >= 2 && len(miningAddress) > 0 {

MineTransactions:

var txs []*Transaction

for id := range mempool {

tx := mempool[id]

if bc.VerifyTransaction(&tx) {

txs = append(txs, &tx)

}

}

if len(txs) == 0 {

fmt.Println("All transactions are invalid! Waiting for new ones...")

return

}

cbTx := NewCoinbaseTX(miningAddress, "")

txs = append(txs, cbTx)

newBlock := bc.MineBlock(txs)

UTXOSet := UTXOSet{bc}

UTXOSet.Reindex()

fmt.Println("New block is mined!")

for _, tx := range txs {

txID := hex.EncodeToString(tx.ID)

delete(mempool, txID)

}

for _, node := range knownNodes {

if node != nodeAddress {

sendInv(node, "block", [][]byte{newBlock.Hash})

}

}

if len(mempool) > 0 {

goto MineTransactions

}

}

}

}

First thing to do is to put new transaction in the mempool (again, transactions must be verified before being placed into the mempool). Next piece:

if nodeAddress == knownNodes[0] {

for _, node := range knownNodes {

if node != nodeAddress && node != payload.AddFrom {

sendInv(node, "tx", [][]byte{tx.ID})

}

}

}

Checks whether the current node is the central one. In our implementation, the central node won’t mine blocks. Instead, it’ll forward the new transactions to other nodes in the network.

The next big piece is only for miner nodes. Let’s split it into smaller pieces:

if len(mempool) >= 2 && len(miningAddress) > 0 {

miningAddress is only set on miner nodes. When there are 2 or more transactions in the mempool of the current (miner) node, mining begins.

for id := range mempool {

tx := mempool[id]

if bc.VerifyTransaction(&tx) {

txs = append(txs, &tx)

}

}

if len(txs) == 0 {

fmt.Println("All transactions are invalid! Waiting for new ones...")

return

}

First, all transactions in the mempool are verified. Invalid transactions are ignored, and if there are no valid transactions, mining is interrupted.

cbTx := NewCoinbaseTX(miningAddress, "")

txs = append(txs, cbTx)

newBlock := bc.MineBlock(txs)

UTXOSet := UTXOSet{bc}

UTXOSet.Reindex()

fmt.Println("New block is mined!")

Verified transactions are being put into a block, as well as a coinbase transaction with the reward. After mining the block, the UTXO set is reindexed.

TODO: Again, UTXOSet.Update should be used instead of UTXOSet.Reindex

for _, tx := range txs {

txID := hex.EncodeToString(tx.ID)

delete(mempool, txID)

}

for _, node := range knownNodes {

if node != nodeAddress {

sendInv(node, "block", [][]byte{newBlock.Hash})

}

}

if len(mempool) > 0 {

goto MineTransactions

}

After a transaction is mined, it’s removed from the mempool. Every other nodes the current node is aware of, receive inv message with the new block’s hash. They can request the block after handling the message.

Result

Let’s play the scenario we defined earlier.

First, set NODE_ID to 3000 (export NODE_ID=3000) in the first terminal window. I’ll use badges like NODE 3000 or NODE 3001 before next paragraphs, for you to know what node to perform actions on.

NODE 3000

Create a wallet and a new blockchain:

$ blockchain_go createblockchain -address CENTREAL_NODE

(I’ll use fake addresses for clarity and brevity)

After that, the blockchain will contain single genesis block. We need to save the block and use it in other nodes. Genesis blocks serve as identifiers of blockchains (in Bitcoin Core, the genesis block is hardcoded).

$ cp blockchain_3000.db blockchain_genesis.db

NODE 3001

Next, open a new terminal window and set node ID to 3001. This will be a wallet node. Generate some addresses with blockchain_go createwallet, we’ll call these addresses WALLET_1, WALLET_2, WALLET_3.

NODE 3000

Send some coins to the wallet addresses:

$ blockchain_go send -from CENTREAL_NODE -to WALLET_1 -amount 10 -mine

$ blockchain_go send -from CENTREAL_NODE -to WALLET_2 -amount 10 -mine

-mine flag means that the block will be immediately mined by the same node. We have to have this flag because initially there are no miner nodes in the network.

Start the node:

$ blockchain_go startnode

The node must be running until the end of the scenario.

NODE 3001

Start the node’s blockchain with the genesis block saved above:

$ cp blockchain_genesis.db blockchain_3001.db

Run the node:

$ blockchain_go startnode

It’ll download all the blocks from the central node. To check that everything’s ok, stop the node and check the balances:

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address WALLET_1

Balance of 'WALLET_1': 10

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address WALLET_2

Balance of 'WALLET_2': 10

Also, you can check the balance of the CENTRAL_NODE address, because the node 3001 now has its blockchain:

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address CENTRAL_NODE

Balance of 'CENTRAL_NODE': 10

NODE 3002

Open a new terminal window and set its ID to 3002, and generate a wallet. This will be a miner node. Initialize the blockchain:

$ cp blockchain_genesis.db blockchain_3002.db

And start the node:

$ blockchain_go startnode -miner MINER_WALLET

NODE 3001

Send some coins:

$ blockchain_go send -from WALLET_1 -to WALLET_3 -amount 1

$ blockchain_go send -from WALLET_2 -to WALLET_4 -amount 1

NODE 3002

Quickly! Switch to the miner node and see it mining a new block! Also, check the output of the central node.

NODE 3001

Switch to the wallet node and start it:

$ blockchain_go startnode

It’ll download the newly mined block!

Stop it and check balances:

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address WALLET_1

Balance of 'WALLET_1': 9

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address WALLET_2

Balance of 'WALLET_2': 9

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address WALLET_3

Balance of 'WALLET_3': 1

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address WALLET_4

Balance of 'WALLET_4': 1

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address MINER_WALLET

Balance of 'MINER_WALLET': 10

That’s it!

Conclusion

This was the final part of the series. I could’ve publish some more posts implementing a real prototype of a P2P network, but I just don’t have time for this. I hope this article answers some of your questions about the Bitcoin technology and raises new ones, for which you can find answers yourself. There are more interesting things hidden in the Bitcoin technology! Good luck!

P.S. You can start improving the network with implementing the addr message, as described in the Bitcoin network protocol (link is below). This is a very important message, because it allows nodes to discover each other. I started implementing it, but haven’t finished!

Links: