Building Blockchain in Go. Part 6: Transactions 2

Chinese translations: by liuchengxu, by zhangli1

Introduction

In the very first part of this series I said that blockchain is a distributed database. Back then, we decided to skip the “distributed” part and focus on the “database” part. So far, we’ve implemented almost all the things that make a blockchain database. In this post, we’ll cover some mechanisms that were skipped in the previous parts, and in the next part we’ll start working on the distributed nature of blockchain.

Previous parts:

This part introduces significant code changes, so it makes no sense explaining all of them here. Please refer to this page to see all the changes since the last article.

Reward

One tiny thing we skipped in a previous article is rewards for mining. And we already have everything to implement it.

The reward is just a coinbase transaction. When a mining node starts mining a new block, it takes transactions from the queue and prepends a coinbase transaction to them. The coinbase transaction’s only output contains miner’s public key hash.

Implementing rewards is as easy as updating the send command:

func (cli *CLI) send(from, to string, amount int) {

...

bc := NewBlockchain()

UTXOSet := UTXOSet{bc}

defer bc.db.Close()

tx := NewUTXOTransaction(from, to, amount, &UTXOSet)

cbTx := NewCoinbaseTX(from, "")

txs := []*Transaction{cbTx, tx}

newBlock := bc.MineBlock(txs)

fmt.Println("Success!")

}

In our implementation, the one who creates a transaction mines the new block, and thus, receives a reward.

The UTXO Set

In Part 3: Persistence and CLI we studied the way Bitcoin Core stores blocks in a database. It was said that blocks are stored in blocks database and transaction outputs are stored in chainstate database. Let me remind you what the structure of chainstate is:

'c' + 32-byte transaction hash -> unspent transaction output record for that transaction'B' -> 32-byte block hash: the block hash up to which the database represents the unspent transaction outputs

Since that article, we’ve already implemented transactions, but we haven’t used the chainstate to store their outputs. So, this is what we’re going to do now.

chainstate doesn’t store transactions. Instead, it stores what is called the UTXO set, or the set of unspent transaction outputs. Besides this, it stores “the block hash up to which the database represents the unspent transaction outputs”, which we’ll omit for now because we’re not using block heights (but we’ll implement them in next articles).

So, why do we want to have the UTXO set?

Consider the Blockchain.FindUnspentTransactions method we’ve implemented earlier:

func (bc *Blockchain) FindUnspentTransactions(pubKeyHash []byte) []Transaction {

...

bci := bc.Iterator()

for {

block := bci.Next()

for _, tx := range block.Transactions {

...

}

if len(block.PrevBlockHash) == 0 {

break

}

}

...

}

The function finds transactions with unspent outputs. Since transactions are stored in blocks, it iterates over each block in the blockchain and checks every transaction in it. As of September 18, 2017, there’re 485,860 blocks in Bitcoin and the whole database takes 140+ Gb of disk space. This means that one has to run a full node to validate transactions. Moreover, validating transactions would require iterating over many blocks.

The solution to the problem is to have an index that stores only unspent outputs, and this is what the UTXO set does: this is a cache that is built from all blockchain transactions (by iterating over blocks, yes, but this is done only once), and is later used to calculate balance and validate new transactions. The UTXO set is about 2.7 Gb as of September 2017.

Alright, let’s think what we need to change to implement the UTXO set. Currently, the following methods are used to find transactions:

Blockchain.FindUnspentTransactions– the main function that finds transactions with unspent outputs. It’s this function where the iteration of all blocks happens.Blockchain.FindSpendableOutputs– this function is used when a new transaction is created. If finds the enough number of outputs holding required amount. UsesBlockchain.FindUnspentTransactions.Blockchain.FindUTXO– finds unspent outputs for a public key hash, used to get balance. UsesBlockchain.FindUnspentTransactions.Blockchain.FindTransaction– finds a transaction in the blockchain by its ID. It iterates over all blocks until finds it.

As you can see, all the methods iterate over blocks in the database. But we cannot improve all of them for now, because the UTXO set doesn’t store all transactions, but only those that have unspent outputs. Thus, it cannot be used in Blockchain.FindTransaction.

So, we want the following methods:

Blockchain.FindUTXO– finds all unspent outputs by iterating over blocks.UTXOSet.Reindex— usesFindUTXOto find unspent outputs, and stores them in a database. This is where caching happens.UTXOSet.FindSpendableOutputs– analog ofBlockchain.FindSpendableOutputs, but uses the UTXO set.UTXOSet.FindUTXO– analog ofBlockchain.FindUTXO, but uses the UTXO set.Blockchain.FindTransactionremains the same.

Thus, the two most frequently used functions will use the cache from now! Let’s start coding.

type UTXOSet struct {

Blockchain *Blockchain

}

We’ll use a single database, but we’ll store the UTXO set in a different bucket. Thus, UTXOSet is coupled with Blockchain.

func (u UTXOSet) Reindex() {

db := u.Blockchain.db

bucketName := []byte(utxoBucket)

err := db.Update(func(tx *bolt.Tx) error {

err := tx.DeleteBucket(bucketName)

_, err = tx.CreateBucket(bucketName)

})

UTXO := u.Blockchain.FindUTXO()

err = db.Update(func(tx *bolt.Tx) error {

b := tx.Bucket(bucketName)

for txID, outs := range UTXO {

key, err := hex.DecodeString(txID)

err = b.Put(key, outs.Serialize())

}

})

}

This method creates the UTXO set initially. First, it removes the bucket if it exists, then it gets all unspent outputs from blockchain, and finally it saves the outputs to the bucket.

Blockchain.FindUTXO is almost identical to Blockchain.FindUnspentTransactions, but now it returns a map of TransactionID → TransactionOutputs pairs.

Now, the UTXO set can be used to send coins:

func (u UTXOSet) FindSpendableOutputs(pubkeyHash []byte, amount int) (int, map[string][]int) {

unspentOutputs := make(map[string][]int)

accumulated := 0

db := u.Blockchain.db

err := db.View(func(tx *bolt.Tx) error {

b := tx.Bucket([]byte(utxoBucket))

c := b.Cursor()

for k, v := c.First(); k != nil; k, v = c.Next() {

txID := hex.EncodeToString(k)

outs := DeserializeOutputs(v)

for outIdx, out := range outs.Outputs {

if out.IsLockedWithKey(pubkeyHash) && accumulated < amount {

accumulated += out.Value

unspentOutputs[txID] = append(unspentOutputs[txID], outIdx)

}

}

}

})

return accumulated, unspentOutputs

}

Or check balance:

func (u UTXOSet) FindUTXO(pubKeyHash []byte) []TXOutput {

var UTXOs []TXOutput

db := u.Blockchain.db

err := db.View(func(tx *bolt.Tx) error {

b := tx.Bucket([]byte(utxoBucket))

c := b.Cursor()

for k, v := c.First(); k != nil; k, v = c.Next() {

outs := DeserializeOutputs(v)

for _, out := range outs.Outputs {

if out.IsLockedWithKey(pubKeyHash) {

UTXOs = append(UTXOs, out)

}

}

}

return nil

})

return UTXOs

}

These are slightly modified versions of corresponding Blockchain methods. Those Blockchain methods are not needed anymore.

Having the UTXO set means that our data (transactions) are now split into to storages: actual transactions are stored in the blockchain, and unspent outputs are stored in the UTXO set. Such separation requires solid synchronization mechanism because we want the UTXO set to always be updated and store outputs of most recent transactions. But we don’t want to reindex every time a new block is mined because it’s these frequent blockchain scans that we want to avoid. Thus, we need a mechanism of updating the UTXO set:

func (u UTXOSet) Update(block *Block) {

db := u.Blockchain.db

err := db.Update(func(tx *bolt.Tx) error {

b := tx.Bucket([]byte(utxoBucket))

for _, tx := range block.Transactions {

if tx.IsCoinbase() == false {

for _, vin := range tx.Vin {

updatedOuts := TXOutputs{}

outsBytes := b.Get(vin.Txid)

outs := DeserializeOutputs(outsBytes)

for outIdx, out := range outs.Outputs {

if outIdx != vin.Vout {

updatedOuts.Outputs = append(updatedOuts.Outputs, out)

}

}

if len(updatedOuts.Outputs) == 0 {

err := b.Delete(vin.Txid)

} else {

err := b.Put(vin.Txid, updatedOuts.Serialize())

}

}

}

newOutputs := TXOutputs{}

for _, out := range tx.Vout {

newOutputs.Outputs = append(newOutputs.Outputs, out)

}

err := b.Put(tx.ID, newOutputs.Serialize())

}

})

}

The method looks big, but what it does is quite straightforward. When a new block is mined, the UTXO set should be updated. Updating means removing spent outputs and adding unspent outputs from newly mined transactions. If a transaction which outputs were removed, contains no more outputs, it’s removed as well. Quite simple!

Let’s now use the UTXO set where it’s necessary:

func (cli *CLI) createBlockchain(address string) {

...

bc := CreateBlockchain(address)

defer bc.db.Close()

UTXOSet := UTXOSet{bc}

UTXOSet.Reindex()

...

}

Reindexing happens right after a new blockchain is created. For now, this is the only place where Reindex is used, even though it looks excessive here because in the beginning of a blockchain there’s only one block with one transaction, and Update could’ve been used instead. But we might need the reindexing mechanism in the future.

func (cli *CLI) send(from, to string, amount int) {

...

newBlock := bc.MineBlock(txs)

UTXOSet.Update(newBlock)

}

And the UTXO set is updated after a new block is mined.

Let’s check that it works

$ blockchain_go createblockchain -address 1JnMDSqVoHi4TEFXNw5wJ8skPsPf4LHkQ1

00000086a725e18ed7e9e06f1051651a4fc46a315a9d298e59e57aeacbe0bf73

Done!

$ blockchain_go send -from 1JnMDSqVoHi4TEFXNw5wJ8skPsPf4LHkQ1 -to 12DkLzLQ4B3gnQt62EPRJGZ38n3zF4Hzt5 -amount 6

0000001f75cb3a5033aeecbf6a8d378e15b25d026fb0a665c7721a5bb0faa21b

Success!

$ blockchain_go send -from 1JnMDSqVoHi4TEFXNw5wJ8skPsPf4LHkQ1 -to 12ncZhA5mFTTnTmHq1aTPYBri4jAK8TacL -amount 4

000000cc51e665d53c78af5e65774a72fc7b864140a8224bf4e7709d8e0fa433

Success!

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address 1JnMDSqVoHi4TEFXNw5wJ8skPsPf4LHkQ1

Balance of '1F4MbuqjcuJGymjcuYQMUVYB37AWKkSLif': 20

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address 12DkLzLQ4B3gnQt62EPRJGZ38n3zF4Hzt5

Balance of '1XWu6nitBWe6J6v6MXmd5rhdP7dZsExbx': 6

$ blockchain_go getbalance -address 12ncZhA5mFTTnTmHq1aTPYBri4jAK8TacL

Balance of '13UASQpCR8Nr41PojH8Bz4K6cmTCqweskL': 4

Nice! The 1JnMDSqVoHi4TEFXNw5wJ8skPsPf4LHkQ1 address received reward 3 times:

- Once for mining the genesis blocks.

- Once for mining the block

0000001f75cb3a5033aeecbf6a8d378e15b25d026fb0a665c7721a5bb0faa21b. - And once for mining the block

000000cc51e665d53c78af5e65774a72fc7b864140a8224bf4e7709d8e0fa433.

Merkle Tree

There’s one more optimization mechanism I’d like to discuss in this post.

As it was said above, the full Bitcoin database (i.e., blockchain) takes more than 140 Gb of disk space. Because of the decentralized nature of Bitcoin, every node in the network must be independent and self-sufficient, i.e. every node must store a full copy of the blockchain. With many people starting using Bitcoin, this rule becomes more difficult to follow: it’s not likely that everyone will run a full node. Also, since nodes are full-fledged participants of the network, they have responsibilities: they must verify transactions and blocks. Also, there’s certain internet traffic required to interact with other nodes and download new blocks.

In the original Bitcoin paper published by Satoshi Nakamoto, there was a solution for this problem: Simplified Payment Verification (SPV). SPV is a light Bitcoin node that doesn’t download the whole blockchain and doesn’t verify blocks and transactions. Instead, it finds transactions in blocks (to verify payments) and is linked to a full node to retrieve just necessary data. This mechanism allows having multiple light wallet nodes with running just one full node.

For SPV to be possible, there should be a way to check if a block contains certain transaction without downloading the whole block. And this is where Merkle tree comes into play.

Merkle trees are used by Bitcoin to obtain transactions hash, which is then saved in block headers and is considered by the proof-of-work system. Until now, we just concatenated hashes of each transaction in a block and applied SHA-256 to them. This is also a good way of getting a unique representation of block transactions, but it doesn’t have benefits of Merkle trees.

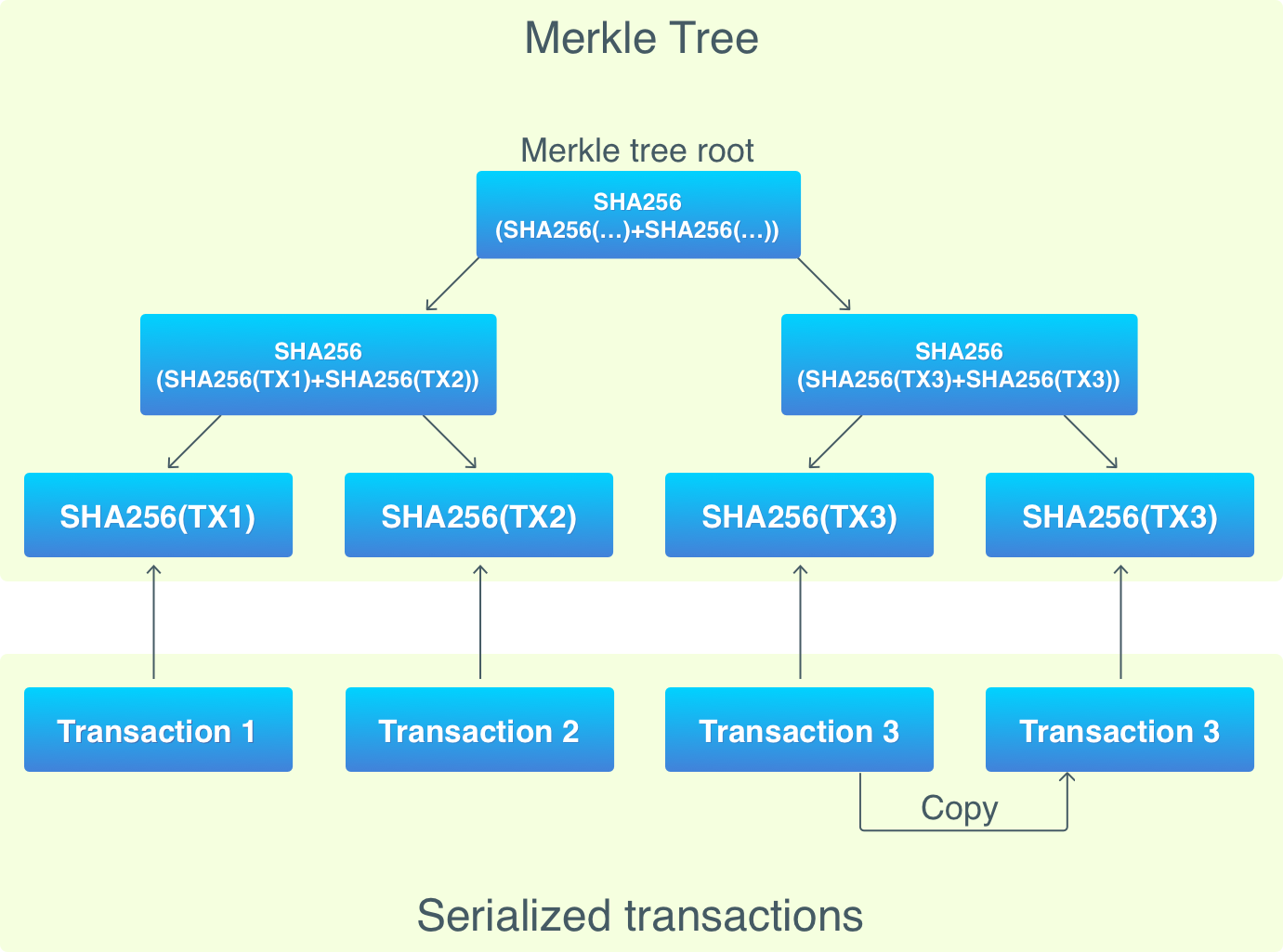

Let’s look at a Merkle tree:

A Merkle tree is built for each block, and it starts with leaves (the bottom of the tree), where a leaf is a transaction hash (Bitcoins uses double SHA256 hashing). The number of leaves must be even, but not every block contains an even number of transactions. In case there is an odd number of transactions, the last transaction is duplicated (in the Merkle tree, not in the block!).

Moving from the bottom up, leaves are grouped in pairs, their hashes are concatenated, and a new hash is obtained from the concatenated hashes. The new hashes form new tree nodes. This process is repeated until there’s just one node, which is called the root of the tree. The root hash is then used as the unique representation of the transactions, is saved in block headers, and is used in the proof-of-work system.

The benefit of Merkle trees is that a node can verify membership of certain transaction without downloading the whole block. Just a transaction hash, a Merkle tree root hash, and a Merkle path are required for this.

Finally, let’s write code:

type MerkleTree struct {

RootNode *MerkleNode

}

type MerkleNode struct {

Left *MerkleNode

Right *MerkleNode

Data []byte

}

We start with structs. Every MerkleNode keeps data and links to its branches. MerkleTree is actually the root node linked to the next nodes, which are in their turn linked to further nodes, etc.

Let’s create a new node first:

func NewMerkleNode(left, right *MerkleNode, data []byte) *MerkleNode {

mNode := MerkleNode{}

if left == nil && right == nil {

hash := sha256.Sum256(data)

mNode.Data = hash[:]

} else {

prevHashes := append(left.Data, right.Data...)

hash := sha256.Sum256(prevHashes)

mNode.Data = hash[:]

}

mNode.Left = left

mNode.Right = right

return &mNode

}

Every node contains some data. When a node is a leaf, the data is passed from the outside (a serialized transaction in our case). When a node is linked to other nodes, it takes their data and concatenates and hashes it.

func NewMerkleTree(data [][]byte) *MerkleTree {

var nodes []MerkleNode

if len(data)%2 != 0 {

data = append(data, data[len(data)-1])

}

for _, datum := range data {

node := NewMerkleNode(nil, nil, datum)

nodes = append(nodes, *node)

}

for i := 0; i < len(data)/2; i++ {

var newLevel []MerkleNode

for j := 0; j < len(nodes); j += 2 {

node := NewMerkleNode(&nodes[j], &nodes[j+1], nil)

newLevel = append(newLevel, *node)

}

nodes = newLevel

}

mTree := MerkleTree{&nodes[0]}

return &mTree

}

When a new tree is created, the first thing to ensure is that there is an even number of leaves. After that, data (which is an array of serialized transactions) is converted into tree leaves, and a tree is grown from these leaves.

Now, let’s modify Block.HashTransactions, which is used in the proof-of-work system to obtain transactions hash:

func (b *Block) HashTransactions() []byte {

var transactions [][]byte

for _, tx := range b.Transactions {

transactions = append(transactions, tx.Serialize())

}

mTree := NewMerkleTree(transactions)

return mTree.RootNode.Data

}

First, transactions are serialized (using encoding/gob), and then they are used to build a Merkle tree. The root of the tree will serve as the unique identifier of block’s transactions.

P2PKH

There’s one more thing I’d like to discuss in more detail.

As you remember, in Bitcoin there is the Script programming language, which is used to lock transaction outputs; and transaction inputs provide data to unlock outputs. The language is simple, and code in this language is just a sequence of data and operators. Consider this example:

5 2 OP_ADD 7 OP_EQUAL

5, 2, and 7 are data. OP_ADD and OP_EQUAL are operators. Script code is executed from left to right: every piece of data is put into the stack and the next operator is applied to the top stack elements. Script’s stack is just a simple FILO (First Input Last Output) memory storage: the first element in the stack is the last to be taken, with every further element being put on the previous one.

Let’s break the execution of the above script into steps:

- Stack: empty. Script:

5 2 OP_ADD 7 OP_EQUAL. - Stack:

5. Script:2 OP_ADD 7 OP_EQUAL. - Stack:

5 2. Script:OP_ADD 7 OP_EQUAL. - Stack:

7. Script:7 OP_EQUAL. - Stack:

7 7. Script:OP_EQUAL. - Stack:

true. Script: empty.

OP_ADD takes two elements from the stack, summarizes them, and push the sum into the stack. OP_EQUAL takes two elements from the stack and compares them: if they’re equal it pushes true to the stack; otherwise it pushes false. A result of a script execution is the value of the top stack element: in our case, it’s true, which means that the script finished successfully.

Now let’s look at the script that is used in Bitcoin to perform payments:

<signature> <pubKey> OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

This script is called Pay to Public Key Hash (P2PKH), and this is the most commonly used script in Bitcoin. It literally pays to a public key hash, i.e. locks coins with a certain public key. This is the heart of Bitcoin payments: there are no accounts, no funds transferring between them; there’s just a script that checks that provided signature and public key are correct.

The script is actually stored in two parts:

- The first piece,

<signature> <pubKey>, is stored in input’sScriptSigfield. - The second piece,

OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIGis stored in output’sScriptPubKey.

Thus, it’s outputs that define unlocking logic, and it’s inputs that provide data to unlock outputs. Let’s execute the script:

-

Stack: empty

Script:<signature> <pubKey> OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG -

Stack:

<signature>

Script:<pubKey> OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG -

Stack:

<signature> <pubKey>

Script:OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG -

Stack:

<signature> <pubKey> <pubKey>

Script:OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG -

Stack:

<signature> <pubKey> <pubKeyHash>

Script:<pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG -

Stack:

<signature> <pubKey> <pubKeyHash> <pubKeyHash>

Script:OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG -

Stack:

<signature> <pubKey>

Script:OP_CHECKSIG -

Stack:

trueorfalse. Script: empty.

OP_DUP duplicates the top stack element. OP_HASH160 takes the top stack element and hashes it with RIPEMD160; the result is pushed back to the stack. OP_EQUALVERIFY compares two top stack elements, and if they’re not equal, interrupts the script. OP_CHECKSIG validates the signature of a transaction by hashing the transaction and using <signature> and <pubKey>. The latter operator is quite complex: it makes a trimmed copy of the transaction, hashes it (because it’s a hash of a transaction that’s signed), and checks that the signature is correct using provided <signature> and <pubKey>.

Having such scripting language allows Bitcoin to be also a smart-contract platform: the language makes possible other payment schemes besides transferring to a single key. For example,

Conclusion

And that’s it! We’ve implemented almost all key feature of a blockchain-based cryptocurrency. We have blockchain, addresses, mining, and transactions. But there’s one more thing that gives life to all these mechanisms and makes Bitcoin a global system: consensus. In the next article, we’ll start implementing the “decentralized” part of the blockchain. Stay tuned!

Links: